AC Interview | Rosela del Bosque

Laguna Salada c. 1950

We recently sat down curator, researcher, and cultural practitioner Rosela del Bosque to talk more about her collaborative project, The Family Archive of the Colorado River. She shares more about tracing the deep histories, political incongruities, and intensely personal memories circling the changing ecology of the Colorado River Basin in her creative research. Listen to the full conversation below and read through the transcript for links to additional resources. If you’re on the go, visit Amplify’s Anchor page to stream the discussion on your favorite podcasting platform.

Transcription

Speaker 1: Rosela del Bosque

Speaker 2: Peter Fankhauser

Date of Interview: September 15th, 2022

List of Acronyms: RB = Rosela del Bosque; PF = Peter Fankhauser

[PF] Hello everybody. My name is Peter and today we're talking to Rosela del Bosque who participated in an Alternate Currents panel discussion back in July that dealt with borders and the idea that borders are places where knowledge is produced, circulated, and embodied. Today we're talking to Rosela more about her project, The Family Archive of the Colorado River. Rosela, welcome. It’s great to have you here. Would you mind telling listeners a little bit more about yourself, and the Family Archive of the Colorado River Project?

[RB] Of course. Thank you for the invitation and for giving space for this topic that I'm so passionate about. I'm also eager to hear feedback from your listeners on the other end. As a quick introduction, my name is Rosela del Bosque. I'm a curator and a researcher. I'm based here in Mexicali, Baja California (Mexico), where most of my projects have sprouted because of the deep affections I have for this territory and its history. Many events have been political and environmental collateral damage in this landscape. My bachelor’s is in art history and I'm now working on my master’s project at Zurich University of the Arts. That research is also actually is deeply related to the family archive. The Family Archive of the Colorado River began mid-pandemic in 2020. And it was due to the political and also personal concerns of cultural agents working in this land. We found it completely urgent and necessary to give voice to water scarcity, to the precarity of the water infrastructure in Mexicali, and the big bold topic of historical claims of dominance and control over the river. It also gives space for non-instrumental experiences. The project it began in that time, and it took different formats. In the end, it's been a really organic project. It's also a long-term project. We're not in a rush to finish because when you begin to unveil water problems and water histories, it gets more and more complex. And that's why we've been trying trace our research and give a bit of context.

The part of Colorado River that I'm talking about is the Delta region, which is the end of the Colorado. And it really is a huge, huge body of water that divides into different little arms, as I like to illustrate it. I'll be talking about some of the names in this place, like the lakes, wetlands, and agricultural regions. The commodification of the river in the last century happened mostly because of the agro-industry. The big corporates that settled here in the beginning of the 20th century, here in Mexicali, gave their names to the Colorado river lands--the Imperial Valley in the in the US and the Mexicali Valley as well. They’re also one of the biggest problem makers because of the of flood irrigation systems.

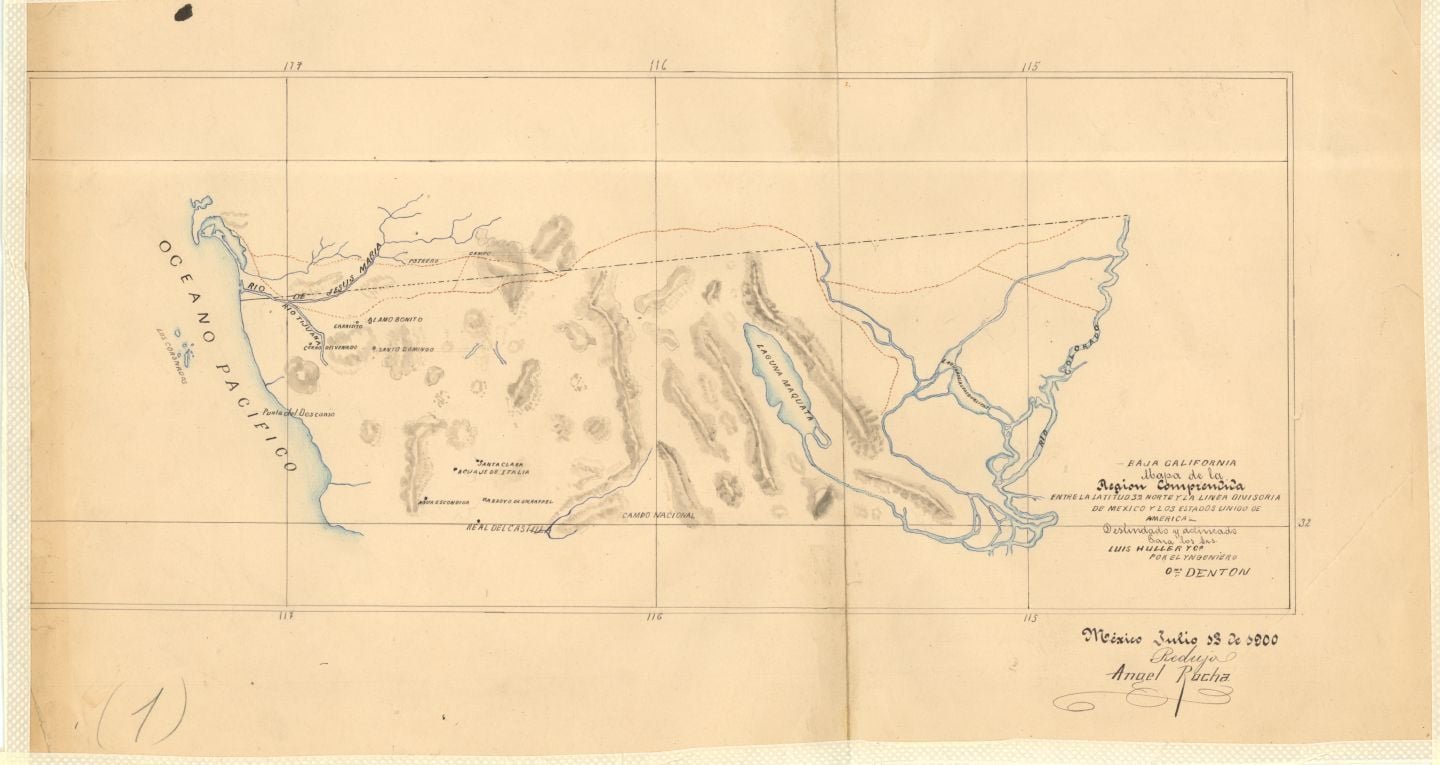

Map of the Colorado River Delta

I’d also like to summarize that the Colorado River gone through dispossession and the exploitation extractivism. It's a river that has been constantly pumped, contaminated, dried up in the case of Laguna Macuata, Laguna Salada. It's a history that divides into ancestral communities. The colonizers, on the other hand, the explorers that came here, came with their own gaze of this landscape and of course, named it as a form of dominion. And it's something that we read from different perspectives now. I will talk about some examples like the Gulf of California, the previously named the Sea of Cortez, and Macuata, which is now called Laguna Salada, of course. The Salton Sea is another a big example for us, and it really does have a relationship with our research. This is the part that is a bit different to other archives, this trans trans-border relationship. The US and Mexico really do have an intimate relationship and it's something that has always comes up. But yes, basically, it's a community archive. Lots of archives have been built through communities, which is something that really inspired us. We want this archive to be a more open ended, a more organic archive that positioned histories of colonizers alongside the non-instrumental spiritual, family anecdotes to generate contrasts between those narratives in a more open in that way, unlike a library. We are trying to position and to think of our research methodology as more of an articulation of flux and a more unstable operation in a way.

[PF] The way that you approach archiving pushes against the conventional definitions of an archive and how an archive is meant to function in the sense that you're seeking to position Indigenous peoples’ narratives as central to the history rather than counter narratives, as they're so often seen in Western academic and environmental discourses. Can you talk a little bit more about that aspect of the project?

[RB] Yes, because in the end, ancestral communities are deeply related to water histories. They have a much longer relationship that I, myself, and city people where it's completely guided through the domestic. Those are the histories we're more infatuated with. Also, something that I forgot to mention, the Archive also thinks about the water in the beginning and where it ends. Where it comes from and where does it end up? The Cucapá community, for example, they're in the Delta region, and we’ve had more of a contact with their community but it's complicated addressing issues in our voice that should come from their voice. We’re critical of that kind of also neocolonialism because we are here talking about this history that belongs to them. But we're also trying to give visibility to the topic at a bigger scale and learn a lot from the spiritual relationship the Cucapá have with the river. They called the river, “Father River.” They have this paternal link that we are not trying to exploit. It's complicated in terms of the power relations because of the social socio-economic disadvantages that exist. But, exactly as you said, instead of a counter narrative, that a central thread that runs through the history of the water, and especially in the Delta region. We’re conscious of those kinds of power relations the legacies of colonialism, which I think really unfolds in our research.

Laguna Macuata

We've been studying their archives and reading about the travelers who’ve interacted with the Cucapá since the 16th century. We really want to abstract ourselves from thinking from an anthropological point of view, where Indigenous people are an object of study rather than integral to a place’s history. My relationship, speaking from a very personal point of view, is really limited, because most of our intra-urban bodies of water are now completely vaulted, piped, contaminated, dried up. My relationship was merely with domestic water and the recreational part of water, which is what most of us share. Listening with the Cucapá and learning about their spiritual connection the water and the phenomenology of water as having this constant spirituality helps reveal the more-than-human aspect of water.

[PF] I love that phrasing, “the more-than-human aspect of water.” I feel like that leads into a larger question about the ecological collapse that the Colorado River Basin is facing and how you frame your research around understanding processes of colonization and its long-lasting effects on the relationships between human beings, more-than-human beings, and ecosystems. In your research, have you seen a different understanding around that relationship emerge as the ecosystem changes?

[RB] That's something we’re cultivating. The Family Archive of the Colorado River also has this really important educational objective of reconciling community, water, and political action we want to sprout in the people who attend our workshops or lectures and really nurture these conversations. The project activates through the conversations we have with different agents. And this also comes into question biologists, geologists, and their opinions, the hard and soft facts of the state our bodies of water are in, especially in the Delta region. It’s really complicated to talk only in terms of ecological collapse, which is a fact that we're all facing. Everyone with their own body of water has a story. But we also like to think of hope and what water utopias are possible, as well as speculation, which is also an important aspect in the project--thinking about ecological fragility as means for fictions and alternative paths, alternate futures.

The project is conscious about decolonizing and neocolonialism and the narratives we haven't been told, deep histories. It's been an interesting experience to see people coming to the project and having their ideas about this ecological crisis that we're all facing. We all have a point of view to share. That's something that we are constantly, completely overwhelmed by all of the participation from people. I’ll also say to anyone listening, if you have anecdotes, photography, archive, speculations for the Family Archive of the Colorado River, we're open. It’s an open call that will never end and we're always excited to read new histories. Scientific research can bring stability to other narratives, but we’d rather have the spiritual, non-instrumental inputs than the hard data. It’s something we want to explore, but through a really artistic lens because scientific research is complex and can be very close ended. We're learning, unlearning, and relearning new things about science, which is also something that has nurtured us, as cultural practitioners, curators, artists, architects, etc.

[PF] It really seems like the iterative research methodology you've adopted in building an archive leaves so much space for, like you said, speculation and an open endedness that feels very expansive. Can you talk a little bit more about what a water utopia in the Colorado River Basin looks like for you in this process of visioning and world building through the archive?

[RB] I will give an example. We've had several workshops, and maybe I wasn't like completely clear about it, but we've had different activations and performances before. One workshop delved into it invoking water in Laguna Maquata. And we did that with Abril Hernandez. She came here to Mexicali, for a short residency, and we did a workshop which was open to artists cultural agents, the community in general, anyone who wanted to engage in a workshop about micro histories, anecdotes, the lines that we're always constantly following with the Family. We had several artists in the end, 12 of us working, which was also quite exciting. It's ambitious to expect big crowds in Mexicali, because cultural consumption is a bit different to other cities in Mexico. So, 12 artists were working on the project, and it was three sessions, two in Planta Libre and one exploration in Laguna Maquata. One artist really encapsulated and embodied this idea of what a utopia is. This is why I give the whole context. He did a photo series. His name is Hugo Fermé. He’s a conceptual photographer, based in Mexicali. He also felt this limit. As I said before, I didn't have this huge history of bathing in the Sea of Cortes, or going to the wetlands, or being in the agricultural canals. That was not part of my history. It's something that comes organically and for him. He made a series of photographs that documented washing his face constantly in his house alled NO VAS A DECIRME COMO ENCONTRAR LA CALMA (YOU'RE NOT GOING TO TELL ME HOW TO FIND CALM). For him, bathing is a spiritual experience and that is his connection with water in the space he calls his home something he could activate in any moment.

He also recently made a piece called To Simulate the Rain. He was on his patio, and he put a big towel on the roof, and he would lay there, and little drops of condensation would fall. He was like, this is a way for me to create small micro experiences with the environment, with water. It was also political statement. Mexicali doesn't have a lot of rain throughout the year. The rains come in a really limited way. His piece was saying, I can produce this kind of experience for myself in a really precarious manner. It's an amazing exercise. I think that for me, that's water utopia, not in a sad way of saying maybe we will only produce rain in our houses, but in a way of embracing this care and sensibility around the topic from a very subjective point of view. That is a small seed that was produced in the workshop but a huge thing for us--reflecting on the topic of the water scarcity by giving a very radically soft approach, rather than dramatic, big, bold letters saying, “CASTASTROPHE IS COMING.” It's also thinking of how to embrace and take in the crisis and as Donna Haraway says, “staying with the trouble.” It's thinking in this kind of tentacular manner in terms of environmental fragility and this idea of making with, making kin. Those are the ideas we're also constantly trying to nurture in our projects and our workshops.

Macalpin en rio hardy - 70s

[PF] That's a beautiful response. I feel like those kinds of frameworks of softness and radical care and hospitality sort of run directly counter to, you know, geoengineering and desalinization and cloud seeding and all these things that we read about. Would you mind talking about what's next for the for the family archive of the Colorado River Project?

[RB] Well, this year we got a grant from Patronato de Arte Contemporáno, which is an institution involved in supporting curatorial projects and artistic research in Mexico City. We applied this year and are developing a project called, Invocaciones al Agua entre los Cerros (Invocation of the Water Between the Hills) that addresses the history of Laguna Salada, which is now the name we see in maps, in cartography, but it was previously known Laguna Macuata and Ja Wi Mak, which is appropriated from the Cucapá and means “the water behind the Sierra Juárez and Cucapá.” There's a there's a really nice picture from the 50s or 60s from an American explorer, also the colonial gaze, that came here and photographed the mountains, and you can see the water between the hills or a reflection from the water in Laguna Macuata. So, the project is really about emphasizing the deep histories in this space, this geopolitical, geologically dense, historically dense space. Laguna Macuata is also the lowest point in all of Mexico in terms of altitude, it's the lowest of all. And what happened is that Laguna Macuata was intermittently flooded by the Colorado during geological, historical times, but because of the building of the dams and the construction, this was of course conditioned, in a way, and stopped happening. The same thing happened with the Salton Sea. It’s the same unfolding of stories.

Laguna Macuata, for this project, we have been working extensively to find references, bibliography, articles, maps, any kind of archival material and overlap in the ecological changes, in the environmental changes, and multispecies shifts. Something that is constantly said in the community is that Laguna Macuata is an infertile space practically, because we only see this the salt, the dirt, but in actuality, microbiological life lives in this site. Laguna Macuata is part of the Cucapá del Mayor territory and its identity. So, we have been learning so many different things about it and returning to the colonial aspect of it. There was an initiative in the 60s called the Three Oceans, between the governor of Baja California and the US state. It was this multi-million-dollar infrastructure plan that pumped water from the Gulf of California, all the saltwater, it would fill Laguna Sala and then it would go to the Salton Sea. So, in a way, they tried to reverse this manmade mistake that was the Salton Sea and flush its waters. But I assume that the water that enters must go back to the ocean and the residual waters from Salton Sea must go back to Laguna Salada and then again to the ocean. Three Oceans is actually being talked about once again, because of the media attention around the Salton Sea and respiratory diseases.

Laguna Salada c. 1950

Laguna Salada, May 2022

So, Invocaciones al Agua entre los Cerros will be a series of gestures that will try to, as the name says, appeal to the water that is gone and trace why water hasn't come back. It’s not so much artistic research based in mourning as political action within the community by the collectives, artists, biologists, and all the people that have been summing up in the discussion around Laguna Maquata. And it's also related deeply to naming, and how we're constantly denouncing the names of bodies of water. It happened with, for example, Mar Bermejo, which is an old name of the Gulf of California. The Spaniards gave it this name because it was a really red kind of ocean. They would say that it was a dirty water and that's why they were aseptic about it. There were minerals from the soils, from the mountains that were carried down by the water and that's a different kind of ecological phenomenon that would create a link for people. Like, the water should be red, but it's not anymore. And now it's just called the Sea of Cortez and the Gulf of California. We're trying to constantly remind ourselves of those different layers of time and space. We're collaborating with Abril as well, once again. She has been a great supporter and collaborator and will be doing a small residency. Right now, we're just finishing up the research phase. Laguna Salada is also a very dangerous area to go. You need a proper car, you need proper lighting, because if you get lost and stuck in the mud or sand, we just don’t want to endanger people for the project. So, once the weather gets better, we're going to start working there. On our social media, we will be sharing more about the artists we will be working with. It will be a collaborative effort and nothing large-scale or monumental. It will be more about not leaving a trace, a bit more ephemeral, and not invading the space.

[PF] All of that sounds really incredible. Before the webpage launches, how can people get in touch follow send you stories, anecdotes, or experiences they've had with the river and the river delta.

[RB] For now, we are always checking our email account, which is archivofamiliardelriocolorado@gmail.com. And we are always open to listening to any kind of anecdote. If people share images, a short companion paragraph would be great--nothing too elaborate, of course. Also, storytelling, fictions, we're eager to listen and hear more about the speculative part of histories. Even newspapers, documents, whatever is related to your own family experiences with water, we’re receiving there. And we now have an Instagram, which will also be attending. You can find all the information, new open calls, the previews of Invocaciones al Agua entre los Cerros. And we will also be creating a summary of some of the histories and uploading excerpts of documents, images, maps, etc. That will be also like a research tool for people, we hope. So, the Instagram is: archivofamiliar_riocolorado. The whole team is bilingual so we can easily also start a conversation, no problem.

[PF] Thank you so much for sharing more about the project and talking with us today, I'm really excited to see how this work continues to unfold. It's been so great hearing more about it.

[RB] Thank you, take care and talk to you soon.

*This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Rosela del Bosque lives and works in Mexicali, Baja California (México). Curator, cultural practitioner and researcher. Her interests focus on the local context and entwine empathy, memory, historical revisionism and reconstructing more-than-human relations in the Colorado river delta landscape. She studied Art History and Curatorial studies at the Universidad de las Américas Puebla. She has completed courses in curatorial practice and contemporary art from Central Saint Martins and the Universitá di Siena. She has collaborated in volunteer programs focused on art education with Museo Jumex and curatorial research with MCASD. She has co-curated projects at La Nana ConArte (Mexico City), with the curatorial collective Base_arriba (Mexicali), Reforma 917 (Puebla) and OnCurating Project Space (Zurich). She is currently an associate curator at Planta Libre (gallery and project space) and pursuing the Master of Advanced Studies in Curating at Zurich University of the Arts.