AC Discussion | Future History: Indigenous Narratives in Art and Media

On June 13th, Paul High Horse, John Paul, and Barbara Robins sat down with Annika Johnson for a conversation about methods and materials Native and Indigenous artists and culture bearers use to reinterpret, revise, and re-present dominant historical narratives that often omit or exclude the Native perspective. They discussed creative working practices that interrogate past erasures, reclaim the present, and vivify Indigenous futures.

Annika Johnson, Barbara Robins, John Paul (from left to right)

Title of Discussion: Future History: Indigenous Narratives in Art and Media Transcript

Panelist 1: Paul High Horse

Panelist 2: John Paul

Panelist 3: Barbara Robins

Moderator: Annika Johnson

Date of Discussion: June 13th, 2025

List of Acronyms: [PHH] = Paul High Horse; [JP] = John Paul; [BR] = Barbara Robins; [AJ] = Annika Johnson; [PF] = Peter Fankhauser

Transcript

[AJ] Thanks everybody for being here and thanks to Amplify Arts for organizing conversations, like this one, that always generate great discussion.

I'm going to introduce our panelists and then we'll hear more about their practices. So we'll go left to right. Paul High Horse is a member of the Siċaŋġu Lakota Nation. At the age of three, his parents moved to the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota so Paul and his siblings could be immersed in their Native culture. He lived on the reservation until he left to attend college at Creighton University in Omaha, Nebraska, where he earned both his bachelor's and his master's degrees. Paul's artistic philosophy incorporates a modern approach to communicate the rich history of his people. He works across media, capturing symbols, traditions, and values inherent to his tribe.

John Paul is a mark maker and a remix artist who uses the techniques of juxtaposition and layering to create new visual narratives from existing works of art. John is also a community arts builder. He works with artists and residents to identify and leverage cultural assets to enhance creative civic engagement. He's part of Amplify’s Alternate Currents cohort currently.

Barbara Robins is a professor in the English department at the University of Nebraska, here in Omaha. She holds a BFA in studio art from the University of Montana, an MFA in English from New Mexico State University, and a PhD in Native American Studies from the University of Oklahoma. She teaches a range of classes, including courses about Native literature, veteran studies, field research, Indigenous food sovereignty. She seeks to open up enough visible space for Native and non-Native students alike to learn about the complex world of Native expression.

Red Cloud Woman in Beauty Shop, 1941

So, I’d like to introduce this discussion with a book called Indians in Unexpected Places by Philip J. Deloria, a professor at Harvard University and a very important thinker in the sphere of Native studies. He opens this book with the image you see on the screen. It shows a woman named Red Cloud Woman, and she's in beauty parlor. This was taken in 1941, and he comments on how this image never fails to elicit a chuckle from people who are looking at it, because there's this seemingly incongruisness of a native person dressed in traditional dress participating in a modern woman's activity. So, his book has a lot to do with why imagery of Native people fixed in the past is so pervasive in American culture.

There's a curator who's brilliant and very funny named Paul Chaat Smith. He curated an exhibition called Americans at the National Museum of the American Indian and it featured pop culture ephemera, advertising, Boy Scouts handbooks, Indian Motorcycles, and other images and objects depicting Native people but not made by Native people. His point was that even though Native people are the first Americans, the vast majority are not present or visible. Paradoxically, Americans are deeply familiar and emotionally connected with Indian imagery, place names, and the influence of Native culture in the fabric of American life.

Camryn Growing Thunder, Santa Fe Indian Market

This photo was taken two years ago at the Santa Fe Indian Market, and reappeared in the work of a young artist named Camryn Growing Thunder. She's a student at the Institute of American Indian Arts right now and she very brilliantly incorporated this into her practice of parfleche bags by sewing into a 1950s style handbag. In it, she reverts the chuckle in this image. Red Cloud Woman isn't the one who's out of place here. It's the now non-Native woman who's painted as an alien on the second bag from the left. A lot of her work features aliens and delves into the history of colonization and also survivance, autonomy, and creativity.

So, artists, educators and culture workers have this powerful ability to challenge pervasive stereotypes about Indigenous people and reimagine a new future. And with that, I’ll ask all of you talk a little bit about what you do and how you're working with historical imagery, with contemporary imagery, and with Native people to interpret and challenge some of these stereotypes. Barbara, would you start?

[BR] And that’s one factor of being here for over 20 years teaching Native American literature. No matter what course I’m teaching, whether it’s an intro course or at the graduate level, I'm always starting at, yes, Native people are still here. The thing that I really want to point out is that there's just, there's so much. There is so much. I always joke that we seem to think that there's five Native American authors and that's all we have to worry about. Usually when I talk to people, they will remember one or two authors. Well, that's great, but what about the other thousand, or so, writers out there currently working?

[JP] My name is John Paul. My father's Chickasaw. My mom is Sac and Fox and Lithuanian. I'm a member of the Chickasaw Nation of Oklahoma, but I look more like my Lithuanian ancestors. In terms of the work, and particularly as it relates to this panel, I'd like to start with the idea of using trickster motifs, trickster images, and humor to disarm as well as inform. That always seems to get people to pay attention to the history that's overlooked and that some people, again, don't think still exists. There's one quote, and it reads something like, “if you're going to tell people the truth, you better make them laugh, otherwise they'll kill you.” And so, a lot of my work is about that effort to build in a little bit of humor. Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun, who is Indigenous First Nations [Cowichan (Hul’q’umi’num Coast Salish) and Okanagan (Syilx) descent] and a beautiful painter who works with humor and trickster motifs, talks about taking something on, be it an injustice or power imbalance, and says, “You can try to wrestle onto the ground; you can try to choke it to death; or you can set a trap for it.” I think in many ways, that's what Native and Indigenous artists often do to ask questions and get people thinking. That's what guides a lot of my work, taking images, turning them on their head, and filtering them through a world of view from my family perspective, which is predominantly Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Sac and Fox.

[AJ] Paul, will you tell us about your work?

[PHH] Sure. I teach seventh through 12th grade art in Fort Collins. I absolutely love what I do. Education was a career change for me. I started off not really knowing what I wanted to do after undergrad and then found my way into education. Actually, it found me. One of my former mentors reached out and asked if I was interested in teaching in western Nebraska I was not qualified and didn't want to move. But long story short, I went to grad school, got my degree and have been teaching ever since. I absolutely love it, and I think there’s a nice back and forth. I learn something and use it for my own practice, or I share with my students, in this ongoing cycle of learning, sharing, and creating. I put a lot of that into my artwork as well.

[JP] Paul has amazing piece where he remixes one of Picasso’s works and puts his father in it, and cultural symbols from his tradition. It's really beautiful. Right now, that image is kind of rocketing across Indian country.

I want to go back to the figure of the Trickster. You know, each tribe has their own interpretation of the Trickster, but in my tradition, the Trickster is a figure that always punches up, never punches down. It will knock you down a peg if you get too big for your britches. It's also a truth teller. A Trickster will always reveal the truth behind what's going on and do it in a sly way.

At the beginning of this book called, The Trickster Shift: Humour and Irony in Contemporary Native Art by Allan J. Ryan, there's, if I'm remembering correctly, an image that reminds me of something my father told me about resiliency and making your way in the world. He grew up in the Chickasaw Nation quite poor, but he became an excellent hunter because he had to hunt for food. Because of his hunting and tracking skill sets, when he was drafted into the war, he was immediately drafted into recon, marine recon, and it was based solely on the fact that he was Native. He was Indian, which highlights the stereotype, this perception that because you're Native, you must be more in tune with the environment.

Because of that, in part, Native Americans have an extremely high death rate in the military because they're often placed in these front-line positions because of the overriding stereotype that they’ll sense danger before anybody else. My father did something like thirty-five enemy missions behind enemy lines and he came back with profound PTSD, but he also taught me a lot about the relationship between humor and resiliency. I remember at one point I was having a really bad time, and he pulled me aside and said, “Why do Indians like the opera? Because in the opera, when a person gets stabbed instead of bleeding, they sing.” And I think he was really trying to impart this wisdom that times will probably always be tough, we need to be resilient, and humor is a form of resiliency. When you're wounded, find a way to sing.

[BR] I’m going to jump in. It’s the educator in me. As someone who teaches veterans literature, that story you're telling about your father is incredibly common. Starting even with World War One, we have an incredibly large number of Native people, both the United States and Canada, serving in our military overseas and the stereotype you’re talking about meant that those guys were always put in to lead reconnaissance and scouting. And of course, overseas, in Europe, what are they going to know about scouting? The number of Native participants in the U.S. military is staggering--over 10,000 in World War One and it goes up from there exponentially.

[AJ] There are real bodily impacts of that come with how Native people are perceived, not just the image, but true life or death consequences, in many cases. What are some of the other ways in which artists are addressing this?

[PHH] Good question. I don't know if this will touch on it or not, but I think for me personally, if I can encourage more visual and cultural literacy through image making, then I'm going to try. With most of my work, it's not just what you're looking at, there's a lot more to it like family histories and symbolic meaning embedded within the image.

Paul High Horse, The Lakota Blind Man’s Meal (2025)

When I started studying art, Pablo Picasso was one of my favorite artists, and his painting, The Blind Man’s Meal, from 1903 really touched me. It wasn't just the piece itself. It was also the time during which he made it, his Blue Period, when he was depressed and sad and had a lot of things going on. I wanted to recreate it, but I didn't know how to approach it, so it sat on the back burner but always came back. And then a few months ago, John Paul approached me and said, “Hey, I've got this idea for an exhibition,” and he asked if I’d participate and it seemed like a good opportunity to pursue it and share this idea I’d been thinking about for so long.

My dad is the subject in the painting. I called him and asked him to pose after I showed him the original. It was important for me that his hair be braided, because the hair is very significant in our culture. They had that bowl in the painting at their house and placed it on the table. I swapped the wine for grape juice and thought about how this historical work could be reimagined through a contemporary Native lens.

[AJ] It's a great painting. And I think you're right. Picasso’s work has been included in art history textbooks. A lot of work by Native artists hasn't. That makes this work meaningful, but also necessary.

Barbara, what are you seeing in literature?

[BR] This is a novel I've had a lot of fun teaching. It’s called Shell Shaker and Leanne Howe is the author. It’s historical fiction, but it's also very magical, very fantastical. We were talking earlier about Tricksters, and in this story, Grandmother Porcupine plays that role. It’s a double murder mystery that takes place in two different centuries: there's this 18th century murder mystery, and then there's the 20th century murder mystery woven together in through the narrative. Porcupine starts in the 18th century, and while she's waiting for things to happen in the 20th century, she has space and time to transform. So, she becomes Sarah Bernhardt, Divine Sarah, a French actress who was born in 1844 and died 1923. Lo and behold, she also shows up to give witness at a trial as part of this double murder mystery in Durant, Oklahoma in 1991. It works and it’s really fun to read this character manipulating time and pulling the strings. She is one of the more enjoyable, playful jokesters I’ve encountered.

[AJ] How do your students respond?

[BR] They're often very puzzled for a big section of the book, but that means they're learning. There’s another thread I’d like to pull at, and I am certainly not a linguist, although I wish I had taken some of those courses way back when, because when I started reading and then initially teaching, everything was published in English. That is not the case anymore. More and more authors are integrating their own language, languages we're losing at such an incredible rate. It's a race, and we don’t know how it's going to turn out. Leanne Howe uses lots of Choctaw. She's not fluent, but she's got it in there and she's going to use it! It's very well translated and it's also contextual. It helps students understand the connection between language and cultural translation. I've noticed that too often when Western readers approach a work of fiction, event this one as fantastical as it is, they want to look at this as an anthropological, historical thing. They have a hard time grasping that this is a novel and a product of the imagination, and I think understanding that is a really important part of acknowledging and appreciating the diversity of contemporary Native literature.

[AJ] Well, we've discussed work so far that crosses temporal divides, working across history, or bringing multiple timelines together. It seems like a way of adapting the future too or questioning the linear progression of time, to reiterate that future, past, and present histories are all with us today.

John Paul, you recently published in Amplify Arts’ Alternate Currents cohort publication, a retelling of The Terror, a World War One era novella. Can you talk more about that work?

[JP] I will, but first, I’d like to go back to something Barbara was saying about language and how language is disappearing. Paul stepped out for a moment, but on Friday next week, we're debuting a documentary that his father made at Joslyn Castle. Paul’s father is head of the language revitalization program at Rosebud. He’s fighting the good fight for sure and it’s really, really good work. We’re also talking about this kind of remixing or repurposing. Paul does beautiful work placing traditional Lakota symbols and motifs in a contemporary context that pushes Indigenous Futurism forward.

In terms of my work, I had this beautiful opportunity to publish a short story through Amplify that I reimagined and illustrated. I like to remix works that are in public domain and indigenize them to a degree. This 1917 story called The Terror is a horror story. To bring up my father again, I think because he was a warrior, because he had been so traumatized by war, he developed a great fondness for horror movies. I think that was because compared to the horror of war, the horror of tribal politics, and cultural genocide, these movies were somewhat of a release for him, an emotional release. He would often laugh at them. It's another survival mechanism. So, the works I like to remix and reinterpret are often in that vein.

The Terror actually inspired the film The Birds. We often think about the human cost of war, but we don’t think as much about the environmental toll and the toll on our animal relatives. In the original story, the animals lose their sense of hierarchy because humans are at war. They're no longer in dominion over the animals. It comes out of a very colonial mindset. So, what if you take that narrative and indigenize it by making the animals powerful and autonomous agents in their own right? In a lot of Indigenous storytelling, the animals come first, people later. What happens when people forget their covenants with the animals, forget the kinship songs, forget the prayers, forget ceremony? The brutality of war opened an interesting path toword recentering the animals and the relationship of care.

In the Chickasaw folk system, aspects of the uncanny and naturalistic horror run deep. A lot of us are probably familiar with Deer Woman, who often shows up when women, and particularly children, are being exploited. Deer Woman brings a bit of that trickster vengeance to those that have committed wrongdoing or harmed the community. In the Chickasaw and Choctaw tribes, we also have Deer Man and he's kind of a protector figure and keeps balance. If you're hunting without respect, or doing ecological damage, Deer Man shows up. Those themes are important to remember when we consider not only Indigenous futures, but our collective future as a species. Do we respect other species? Have we lost our kinships with our animal relatives?

[BR] In the Native lit world, that’s one of the new directions that literary criticism is taking. There’s new emphasis on reading material from the Western cannon from a Native American perspective. Critics are saying, what if we look at Dracula, for example, not through a Eurocentric lens, but rather from an Indigenous point of view? I taught a course called, Teaching Native American Literature, and we read Walt Whitman with that in mind. It turns everything inside out. Daniel Heath Justice is a really amazing literary critic who wrote a book called Why Indigenous Literatures Matter that asks about those Indigenous kinship traditions. How do we learn to be human? How do we become good relatives? How do we become good ancestors? How do we learn to live together?

[AJ] I’m seeing a number of tools here, and one of them is operating within existing genres, which is an interesting thread across your work. It seems that almost every project we’ve discussed is asking something of the viewer, or the reader, or the student. They all ask people to reframe their perspective and challenge their own preconceived notions, specifically around stereotypes of Native people. What's comes next? What are you as creators and educators, asking of your audiences?

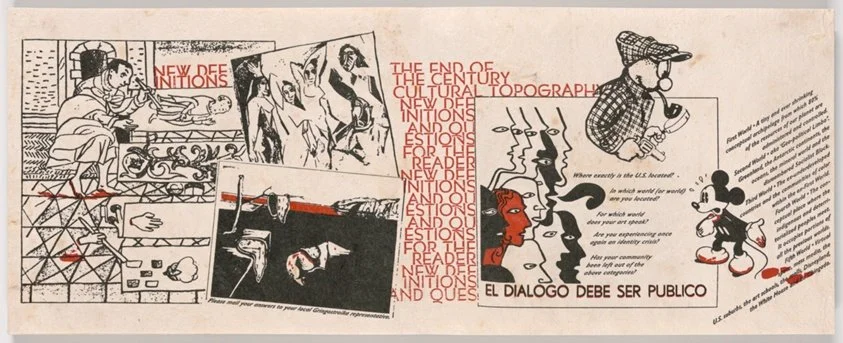

Guillermo Gomez-Pena, Enrique Chagoya, Felicia Rice, Codex Espangliensis: From Columbus to the Border Patrol (2000)

[BR] Well, speaking in terms of what we ask of an audience, there’s an amazing book called Codex Espangliensis: From Columbus to the Border Patrol that started off as an artist book, a work of art, that was then picked up by City Lights Publishers in San Francisco. It’s by Guillermo Gomez-Pena, Enrique Chagoya, and Felicia Rice who worked to fuse pre-Hispanic graphics, postcolonial figures, and superheroes popular in US American culture within the format of a Mayan codex, a fold out book. It's a difficult read because it's multilingual and it's typeset in a way that intended to complicate the reading experience. It's visual, but it's incredibly polyvocal. It’s satirical and complex and angry about border politics. At the same time, it's really fun to read.

Complicating the notion of legibility is something I do in my own work as well. In a project, which is still in process, called Culture Capture, I embedded elements associated with Indigenous cultures and trap them between the pages of the book. There’s ribbon, there's feathers, there's horsehair embedded in the paper itself. I'm hoping to work a lot more with language and legibility, especially because a lot of Native languages are written in ways that we, as Westerners, are not used to encountering. That creates a different kind of visual problem. So, in a long-winded answer, as someone who doesn't speak these languages very well, I see the relevance and the ethical importance of paying more attention to language. We should be listening better. We should be collaborating more and working to revitalize language before it really is forever illegible and lost all together.

[JP] Listening and collaborating. That’s good guidance, Barbara.

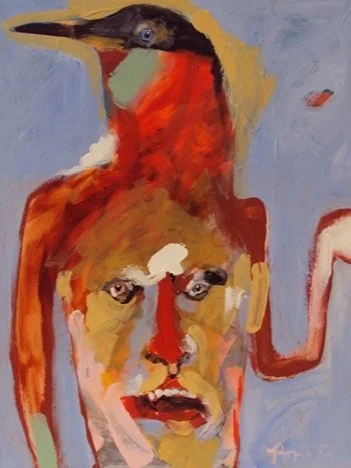

I want to bring up Rick Bartow’s work. He was a warrior as well and a big influence in my life. He was a contemporary of my father, who is also a visual artist. His work is beautiful, and it fits into the question Annika asked in terms of what's next. His work, from an Indigenous perspective, expresses the idea that what is the future is the past, what is the past is present, what is the past is also future. Time isn’t linear. It's happening all at once.

Rick Bartow, Bird Dream (2008)

Cannupa Hanska Luger, Midiigaadi. Light Bison (2019)

Virgil Ortiz, a ceramicist, storyteller, filmmaker, also embraces the idea of Indigenous Futurism by telling the story of the 1680 Pueblo Revolt in his work to people who might not necessarily know that history. The New Mexico Pueblos revolted against the Spanish colonial rule and drove out the settlers for a time before they reached an uneasy peace. Working with that history is his way of projecting it deep into the future by asking viewers to consider the possibility of a post-colonial world more deeply. When you get into that mindset, you can play around with all these motifs too in Indigenous sci-fi and design. What is a Hopi blanket going to look like in 3025, you know? The past is the future, and the future is the past. Back to what we talked about earlier, if you're going to tell somebody the truth, you better make them laugh and you better make them think.

[AJ] I'm working with an artist named Cannupa Hanska Luger, and he has an ongoing series called Future Ancestral Technologies. He creates artwork and scenarios that feel apocalyptic, but energizing and optimistic at the same time. He said he no longer uses the word “history.” He uses the word “continuum.” My co-curator and I have started replacing the word “history” with “continuum” more and more because when we talk about art history, the discipline I was trained in, and swap it for art continuum, the knees buckle underneath the field, the entire structure for it.

[Barbara Robins] Don't forget, they dubbed Star Wars in Diné bizaad, the language of the Navajo or Diné people. English subtitles for a change.

I come from a family of photographers. Anybody familiar with cyanotypes? It's a form of contact printing and I’ve been making cyanotypes from negatives in my family collection as one way of interrogating settler histories. I wanted to include it because I think what we're trying to do here is open up new kinds of conversations. Another book I’d like to bring up is The Cost of Free Land: Jews, Lakota and an American Inheritance by Rebecca Clarren. Her family history is within an hour’s drive of where my family homesteaded in South Dakota. So, our family histories have displaced other families, they’ve have displaced other cultures. I say that because here we are in this moment we're calling the culture wars. I'm going to start calling it the “empathy wars” because we're struggling to understand other points of view. There was this a pendulum shift not too long ago where more people were open to including Indigenous voices and doing land acknowledgements and speaking more respectfully about Native culture. But we still have to have these really hard conversations about the legacies of settler colonialism. It's an environmental issue, it's a cultural issue, it's a linguistic issue. So, I've been really thinking about how I, as a non-Native person involved in Native American art and literature, can participate in these conversations without being an appropriationist and that's part of what I'm trying to do with the cyanotypes.

They’re part of a bigger project that unpacks my family history and its place in Native American history. Until 1917, the historical record of South Dakota said that my family homesteaded on the site of the Battle of Slim Buttes, which was the first skirmish after Custer was killed. That became something of a family obsession, so I’m going through tons of family documents and photos to better understand that history and how to acknowledge it.

Barbara Robins, Gill, South Dakota: A homestead in the Slim Buttes 1910 – 1948 (2025)

[AJ] This is an awesome packed house. Let’s open the floor. Does anybody have questions?

[Audience Member] Barbara, can you talk more about you’re thinking about bringing settler histories into the present in a way that helps people talk about it rather than retreat from it?

[BR] I’ve shepherded so many students through these discussions. It’s a very common feeling to want to pull back or retreat from them. If you're from a settler family, which the vast majority of us are, then you have to deal with problematic histories and choices in your family. And retreat is a very first and natural response. Don't stay there. That's what I tell my students. Acknowledge it and learn more and then move on; just don’t’ stay there. You're going to process it as part of your family history, and then, and then talk to people and learn to open yourself up to new perspectives.

[AJ] I think that’s a great place to end the discussion for now. Thanks everybody for coming and we’ll see you again soon.

*This transcript has been edited for length and clarity. Alternate Currents programming is possible with support from The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, the Nebraska Arts Council, and Metropolitan Community College.

About the Panelists:

Paul High Horse Paul High Horse is a member of the Sicangu (Sičháŋǧu) Lakota tribe. Son of a Lakota father and Italian mother, Paul was born in New Jersey; however, at the age of three, his parents moved to the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota so Paul and his siblings could be immersed in their native culture. He lived on the reservation until he left to attend college at Creighton University in Omaha, Nebraska, where he earned both his bachelor's and master's degrees. Paul’s artistic philosophy incorporates a modern approach to communicate a rich historical context of the Lakota people. His art captures the symbols, traditions, and values inherent to the Lakota tribe. His work also explores different media including acrylics, archival pens, watercolor, and ledger paper. Paul currently teaches 7-12th grade art at Fort Calhoun Community School in Fort Calhoun, Nebraska, but resides in Council Bluffs, Iowa.

John Paul is a mark-maker and a “re-mix” artist who uses the techniques of juxtaposition and layering to create new visual narratives from existing works of art. John is also a community-arts-builder who works with artists and residents to identify and leverage cultural assets to enhance creative-civic engagement.

Baraba Robbins, PhD is an Associate Professor in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. She holds a BFA in Studio Art from the University of Montana, a MA in English from New Mexico State University, and an PhD in Native American Studies from the University of Oklahoma. Her teaching areas are Native American Literature, Visual, and Performing Arts; Research and Writing in Native American Topics; Veterans Literature; and Medical Humanities. Her research areas are Contemporary Native American Literature, Visual, and Performing Arts; 9/11; Historical Trauma and PTSD; and Indigenous Language Revitalization.

About the Moderator:

Annika K. Johnson, PhD is the Stacy and Bruce Simon Curator of Native American Art at the Joslyn Art Museum where she is developing installations, programming, and research initiatives in collaboration with Indigenous communities. Her research and curatorial projects examine nineteenth-century Native American art and exchange with Euro-Americans, as well as contemporary artistic and activist engagements with the histories and ongoing processes of colonization. Annika received her PhD in art history from the University of Pittsburgh in 2019 and grew up in Minnesota, Dakota homelands called Mni Sóta Makoce.