AC Response | Emily Andersen

Emily Andersen is a co-founding Principal of DeOld Andersen Architecture, and guest lecturer at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. We asked her to share some thoughts about the evolution of Omaha’s built environment and the degree to which it hospitably welcomes those working in creative fields. Read her response below and join the conversation by leaving your comments.

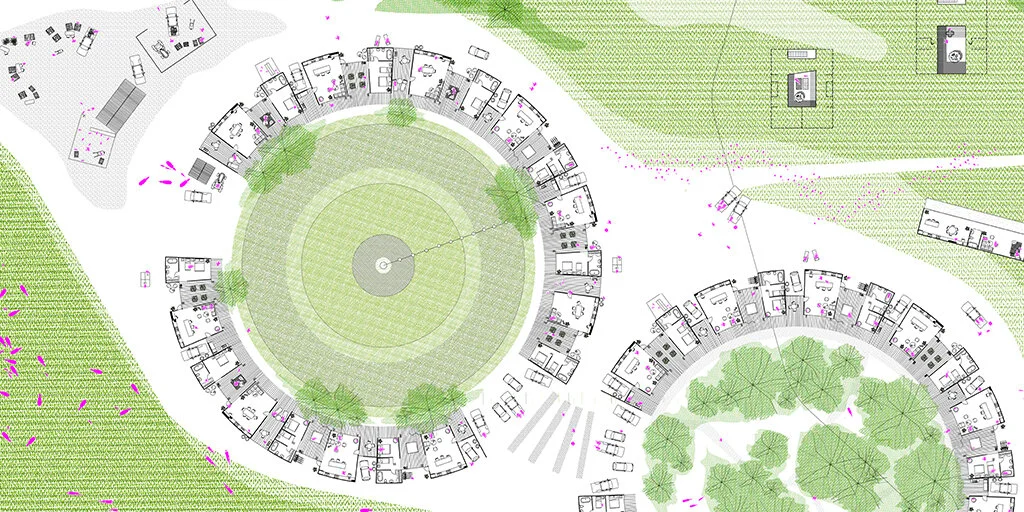

DeOld Andersen Architecture, Settlement Patterns, 2018

In the last few years, a conversation about affordable housing has started to take place in Omaha. Like in other cities, the return to the urban core and a shortage of housing has meant that housing in this part of the city has become expensive. Omaha is just beginning to see gentrification, and with that an increase in the cost of housing within its urban areas. While affordability needs to be addressed, there is also a question of how the new housing is suited to the people that need housing whether it is a single family house, an apartment, or other attached dwelling type. How does it actually perform to support an individual or family? And in that sense, what would a model look like that is designed for people who make and do stuff in their own homes, artists and other “creators” (those employed in creative fields, entrepreneurs, or simply individuals involved in creative pursuits)?

Most housing models really suit a small demographic of individuals. Housing is a product. And the shape and form of it is driven by the market. It is both driven simultaneously by derivative trends (as seen on HGTV) and extremely conservative dynamics. The financing involved for building a house or apartment building mean that lenders want to develop models that are proven. Meaningful innovation in housing is difficult for this reason. The idea of any deep thinking about how you live and occupy a space and any resultant experimentation in design has no place in the market.

Models of housing are based on marketing a lifestyle. The first suburbs marketed “modern” houses with the latest ideas on what the American household looks like, a particularly sanitized idea that enforced domesticity and the nuclear family. Most homes still follow this pattern, and truly radical ideas are adopted very slowly for mass consumption. An example of this is the idea of the “open plan”, seemingly novel as described by HGTV, is an idea that was introduced more than 100 years ago by modernist architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier. Likewise new apartments are marketed to lifestyles, promoting amenities such as rooftop pools, gyms, and lounges. The lifestyle that is promoted is more about being entertained than about how your apartment supports activities that involve making.

DeOld Andersen Architecture, Settlement Patterns, 2018

Can your dwelling be a useful tool to support involvement and engagement in the act of making? Of course, live-work art studios exist in Omaha. But it would be interesting if more models existed that developed ideas further on a larger scale. Could the City of Omaha incentivize developers to develop new models of housing for artists and “creators”?

This would require Omaha’s leaders to understand the creative fields as economic generators for the city, and that developing or incentivizing the development of housing for artists and “creators” would be an economic development tool.

Engaging artists and makers in this conversation could generate strategies for innovative design. Should we assume the ideal space is a raw box with good light? Better understanding the diversity of media used and the creation process might result in more nuance. Omaha’s housing market does not offer a large variety of options of housing types, and having this conversation could broaden the typology and create new models that address artists or anyone using their home to support entrepreneurial or creative endeavors.

Emily Andersen is a co-founding Principal of DeOld Andersen Architecture, and guest lecturer at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. She oversees the design and technical development of DAA’s projects. Prior to founding DAA in 2010, she was an Associate at Slade Architecture in New York City, where she worked on a variety of residential and commercial projects, along with public work for the City of New York. Emily received her BSAS and MA from the University of Nebraska- Lincoln, and is licensed to practice in the State of Nebraska. She’s been a visiting critic at Texas Tech University in both Lubbock, TX and Montreal, QC, NYIT in Old Westbury, NY, Parsons The New School for Design in New York, NY, the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, NY, and South Dakota State University in Brookings, SD. She served as a juror on the South Dakota Chapter AIA Awards. In 2015 she was a Fellow of the New Leaders Council, and currently is on the Board of Directors for Big Muddy Urban Farm.